Viral Tumblr Thread Explains Reasons Kids Don’t Play Outside Anymore

It seems like when I was a kid, we played outside a lot. I grew up with a very awesome swingset my dad built us AND we backed up to the woods, so we’d tromp down to a nearby river, swing on the swings, and generally do “kid stuff” outside of our house.

But I’ll be real with you: it sure doesn’t look like kids DO that kind of stuff anymore. Right?

Maybe it’s the internet. Maybe it’s social media.

Not so, says Tumblr.

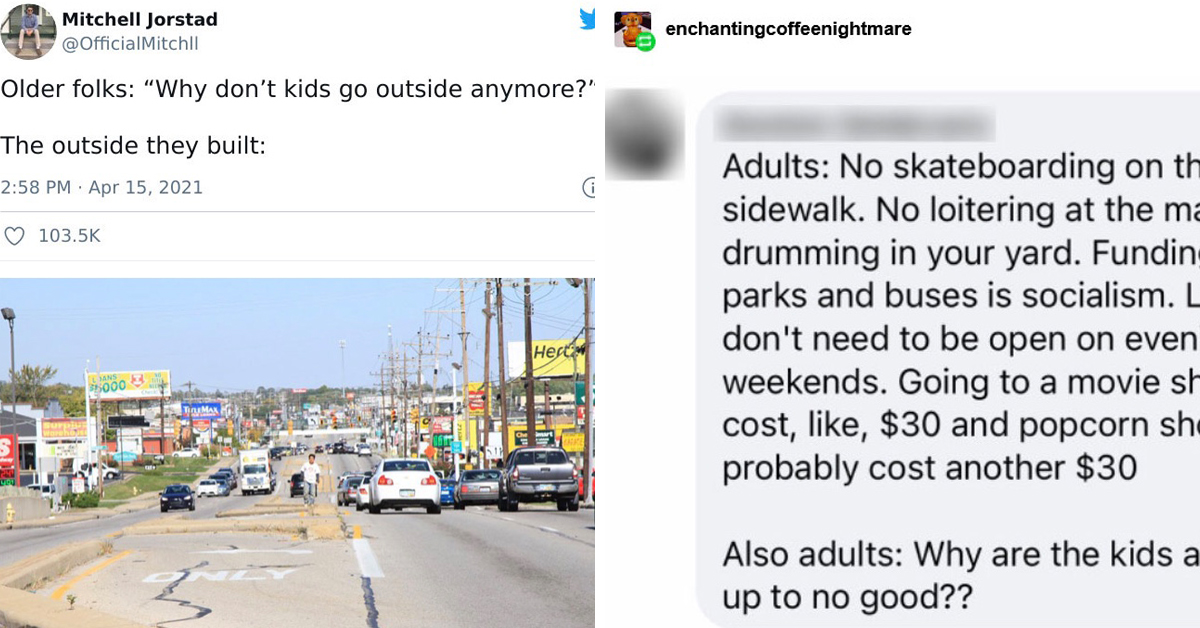

A tweet from Mitchell Jorstad asked why kids don’t play outside anymore than jokingly shows a kid walking down a busy street in the median. The tweet crossed over to Tumblr, where people responded quickly.

And pretty soon, as Tumblr does, we started getting long explanations of why kids don’t go outside anymore.

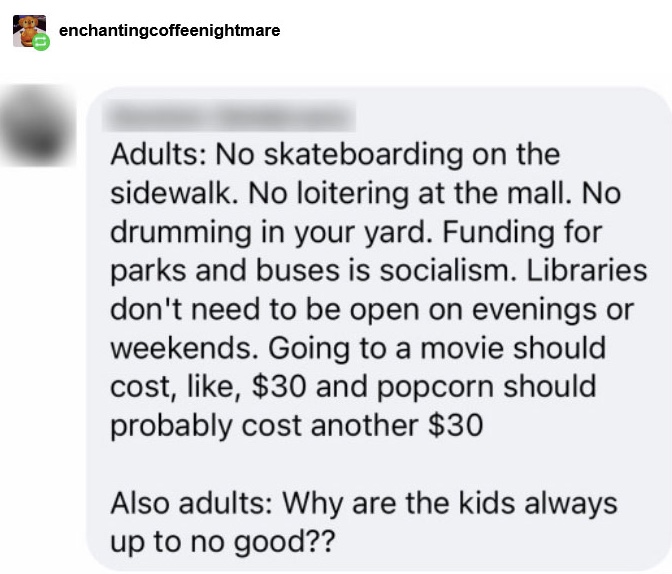

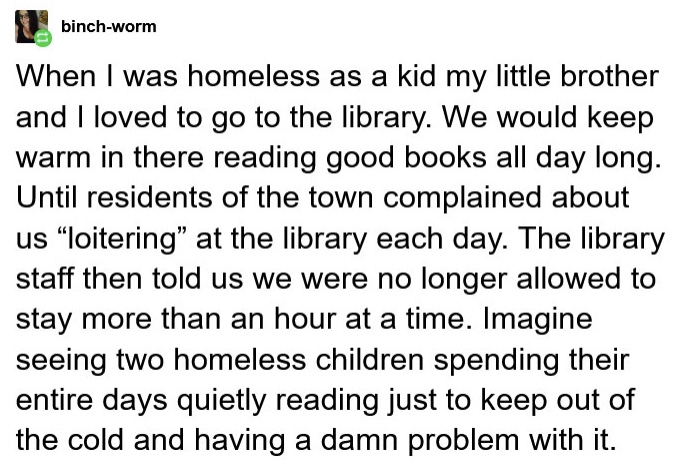

Enchantingcoffeenightmare shared that everything is forbidden or too expensive. Binch-worm told a story about how as a homeless child, she stayed in the library as much as she could. Until people complained…

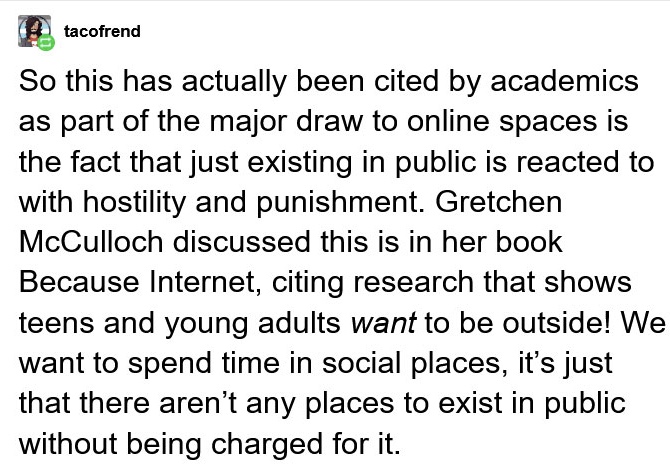

And then came tacofrend, who shared some research study results. The user says that academics have shown that a big reason people head to online spaces is because just BEING in public is “reacted to with hostility and punishment”.

Here’s the sad part: kids WANT to be outside, tacofrend says Gretchen McCulloch wrote in her book. But there aren’t places to do it.

Because Internet, McCulloch’s book, became a touchstone of the conversation. Allthingslinguistic came in with the a relevant passage from Because Internet:

Even the fact that teens use all kinds of social networks at higher rates than twenty-somethings doesn’t necessarily mean that they prefer to hang out online. Studies consistently show that most teens would rather hang out with their friends in person. The reasons are telling: teens prefer offline interaction because it’s “more fun” and you “can understand what people mean better.” But suburban isolation, the hostility of malls and other public places to groups of loitering teenagers, and schedules packed with extracurriculars make these in-person hangouts difficult, so instead teens turn to whatever social site or app contains their friends (and not their parents). As danah boyd puts it, “Most teens aren’t addicted to social media; if anything, they’re addicted to each other.”

Just like the teens who whiled away hours in mall food courts or on landline telephones became adults who spent entirely reasonable amounts of time in malls and on phone calls, the amount of time that current teens spend on social media or their phones is not necessarily a harbinger of what they or we are all going to be doing in a decade. After all, adults have much better social options. They can go out, sans curfew, to bars, pubs, concerts, restaurants, clubs, and parties, or choose to stay in with friends, roommates, or romantic partners. Why, adults can even invite people over without parental permission and keep the bedroom door closed! (page 102-103)

That user also suggested It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens by danah boyd. There were some excepts of that book shared too:

I often heard parents complain that their children preferred computers to “real” people. Meanwhile, the teens I met repeatedly indicated that they would much rather get together with friends in person. A gap in perspective exists because teens and parents have different ideas of what sociality should look like. Whereas parents often highlighted the classroom, after-school activities, and prearranged in-home visits as opportunities for teens to gather with friends, teens were more interested in informal gatherings with broader groups of peers, free from adult surveillance. Many parents felt as though teens had plenty of social opportunities whereas the teens I met felt the opposite.

Today’s teenagers have less freedom to wander than any previous generation. Many middle-class teenagers once grew up with the option to “do whatever you please, but be home by dark.” While race, socioeconomic class, and urban and suburban localities shaped particular dynamics of childhood, walking or bicycling to school was ordinary, and gathering with friends in public or commercial places—parks, malls, diners, parking lots, and so on—was commonplace. Until fears about “latchkey kids” emerged in the 1980s, it was normal for children, tweens, and teenagers to be alone. It was also common for youth in their preteen and early teenage years to take care of younger siblings and to earn their own money through paper routes, babysitting, and odd jobs before they could find work in more formal settings. Sneaking out of the house at night was not sanctioned, but it wasn’t rare either. (page 85-86)

From wealthy suburbs to small towns, teenagers reported that parental fear, lack of transportation options, and heavily structured lives restricted their ability to meet and hang out with their friends face to face. Even in urban environments, where public transportation presumably affords more freedom, teens talked about how their parents often forbade them from riding subways and buses out of fear. At home, teens grappled with lurking parents. The formal activities teens described were often so highly structured that they allowed little room for casual sociality. And even when parents gave teens some freedom, they found that their friends’ mobility was stifled by their parents. While parental restrictions and pressures are often well intended, they obliterate unstructured time and unintentionally position teen sociality as abnormal. This prompts teens to desperately—and, in some cases, sneakily—seek it out. As a result, many teens turn to what they see as the least common denominator: asynchronous social media, texting, and other mediated interactions. (page 90)

Basically, kids WANT to hang out in person and outside, but things like suburban isolation and overbooked schedules don’t allow them the freedom to do so. Kids prefer online because it comes without the burden of scheduling and they have more freedom to interact — no parents!

The thread has circled over 100,000 times on Twitter and nearly 200,000 times on Tumblr with almost 7,000 upvotes, so it definitely struck a chord!